DESIGNER NOTES

Introduction

I began designing my own roleplaying games because I was not satisfied with what was available for fantasy. Fantasy is the most overdone genre in the world of RPGs, yet no fantasy game that I had played did exactly what I wanted.

I want a fantasy game that is in the middle of the great RPG debates. I want a balance between realism and heroism. I want a balance between roleplaying and hack-n-slash. I want a game that is easy to learn, with minimal mass and implementation complexity, but has plenty of variety in character type and actions. I want players to have a number of different tactical options without having to deal with too much detail - no exact maps, no longs lists of spells or manuevers, minimal bookkeeping. I wanted a game that felt like low fantasy, but where sorcerers could still deal out some whoopass.

I claim no originality in my mechanics. I have taken elements from all of my favorite games (HERO, WEG d6 Classic, D&D), some that I haven't even played (FUDGE), and some that I don't even like (GURPS, D&D). I started by trying to combine the best parts of AD&D 2e and Champions 4e, yet wound up with mechanics that look more like WEG d6 than anything else. Go figure.

The setting, likewise, is nothing more than a mishmash of things I like. It began with two basic premises: Arthur C. Clarke's assertion that "any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic" and the various fringe theories about ancient astronauts creating the human race by combining their DNA with that of apes. I leave it vague - are the gods really gods, or merely powerful aliens? Is there a difference? Is magic really magic, or just transhuman technology? Does it matter?

Take these premises, throw in elements of Conan, Cthulhu, Paradise Lost, Sumerian mythology, and The Twilight Zone, and you get my setting. It wound up looking a little like Stargate, which is another thing that I never intended. Go figure.

Character Generation

I always loved the character generation of HERO. I loved the fact that I could place my points anywhere I wanted to create exactly the character I had in mind.

I wanted something similar in my game, but I didn't want quite the level of customization that HERO is capable of. I wanted my fantasy world to have a least a few distinct niches that reflected the particular flavor of the setting. I also wanted character creation to be much simpler - I don't find HERO's chargen mechanics to be that daunting, but many fellow gamers have fled in terror at the sight of fractions.

I wanted to distill the core attributes into only those that were most necessary to describe an adventurer. I decided to make attributes very broad because most players I have known tend to choose basic archetypes for their fantasy characters - rarely does anyone create a fighter who is strong but not tough, or a rogue who is quick but not perceptive. I decided to leave specialization to the skills.

I wanted there to be symmetry between physical and mental attributes. I wanted them to be equal in number and symmetrical in purpose. I chose Strength to represent physical power, Dexterity to represent physical speed, Willpower to represent mental power, and Intelligence to represent mental speed.

My decision to leave out attributes and skills related to social dynamics was deliberate. I have never liked stats such as Charisma, Presence, or Beauty. At best, they interfere with the roleplaying aspect of the game. Some players use them as a crutch - why try to convince someone of something through roleplaying when a Charisma roll can make the whole scene pass by? At worst, players simply ignore them in favor of more adventure-worthy skills, which forces those players who want to be charismatic to be less effective at adventuring.

I chose to ignore them. If you want to be beautiful and dashing, fine. If you would rather be ugly and scary, good. There are advantages and disadvantages to both.

I wanted skills to be broad. I dislike games with too much mass in the rules. I dislike hyper-specialized characters. It never made sense to me that someone could be the best swordsman in the world, yet completely useless with any other weapon. With broad skills, even characters that choose to specialize in just one or two skills are at least specialists in a field, rather than a subset of a subclass of a profession.

The skill list focuses on adventuring skills while greatly abstracting non-adventuring skills. I did this because I wanted those who wished for their character to be a talented craftsman or scholar to be still able to compete in the adventuring arena. All craft skills, from blacksmithing to shoemaking, are considered part of a single skill: Craftsmanship. All academic skills are considered part of Scholarship. This is not realistic, but I think it's fun.

Note that this is meant primarily for player characters - most NPCs will be specialists.

I wanted sorcery to be skills just like any other. I didn't accomplish this entirely - I found it necessary to require Gifts for the use of sorcery simply to prevent every character from having the ability. Gifts also allow for alien abilities that cannot properly be called skills.

Attributes had to be much more expensive than skills to prevent players from ignoring skills. Why improve one's Archery, when improving your Dexterity will improve that and all of your other physical skills at once? I chose a ratio of 10:1, which means that players will only improve their attributes to the point that they wish for at least ten of their skills to be, and will specialize thereafter. This is especially true during a campaign, as experience is given out in smaller doses that players will want to use right away.

I claim in the text that every +2 to an attribute or skill makes that stat twice as effective. This is mostly for flavor (though the probabilities are not entirely inaccurate). The point in calling +2 "twice as effective" is to make it so that the probabilities between two conflicting characters are the same if the ratios of their skills are the same, regardless of the absolute numbers involved.

What this means, in English, is that the probabilities of a contest between two characters of skills 2 and 4 are the same as those of a contest between two characters of 4 and 6, or 6 and 8, or any other difference of two, because in each case one character is "twice as effective" as the other. Similarly, the probabilites of 2 vs 8 are the same as 8 vs 14. This allows the mechanics to scale to godlike proportions if necessary - if AN, great god of the heavens, is twice as strong as UTU, god of the sun, and UTU has a Strength of 20, then AN will have a Strength of 22.

The cost of attributes and skills increases faster as the levels get higher (specifically, it follows a quadratic growth curve). The reason for this is simple - I wanted for attributes and skills to be open-ended, limited only by the number of points the players were willing to put into them. At the same time, I didn't want annoying players to put every last point they got into a single skill. Such actions would result in the character being a god at exactly one thing and worthless at everything else.

The current cost scheme does not mesh perfectly with the geometric progression of effectiveness spoken of in the flavor text. This is because a geometric progression cost would quickly lead to ridiculously high costs for everything. As it is, the costs increase at a rate that gives diminishing returns, but not so dramatically that all characters will be generalists.

This cost scheme also means that it is painless for a character to learn a small amount about any skill. Mastery, on the other hand, requires dedication.

Finally: some may be confused by the secondary attributes. Some players might think it unrealistic that their big brawny warrior has the same Health and Stamina as a scholar. Those who think this should look at the secondaries from the opposite direction to see what actually occurs when characters get hurt.

It is easiest to illustrate by example. Take two characters, Bob and Fred. Bob has a Strength of 0 - completely average. Fred has a mighty Strength of 4. What happens when either character is hit by an attack that does 5 damage? After one hit, Bob will be at the Hurt level of Health and down 5 Stamina. After two hits, he will be unconscious. Fred, on the other hand, will have to be hit ten times by the same attack before he will fall, and even then he will still be at the OK Health level. An attack that does 10 damage will knock Bob out in one hit and make him Wounded - Fred will take two such hits before falling and will only be Hurt.

So, though secondary attributes are the same for every character in absolute numbers, different characters are still able to take more or less punishment based on their Strength, Willpower, and any armor or charms they might be wearing.

System Mechanics

I wanted the mechanics of my game to be easy to learn and simple to execute, yet powerful in possibility. I wanted a quick core mechanic that could be used for everything. I wanted the core mechanic to contain enough randomness that characters would have a chance against more powerful opponents, but not so much randomness that skill levels wouldn't matter.

I chose opposed rolls of 2d6 + Attribute + Skill as the core mechanic for several reasons:

The last point may need some justification. Those who have studied dice probabilities in the past will object that the distribution of two dice added together is triangular, not bell-shaped. So it is. However, this core mechanic uses four dice, not two!

Run the numbers and you will find that opposed rolls of 2d6 are functionally equivalent to rolling 2d6 - 2d6 or 4d6 - 14. All three methods involve four dice and give a probability distribution ranging from -10 to 10, centered on zero, with 89% of the rolls falling between -5 and 5. This means that a character has barely a five percent chance of besting an opponent whose ability level is five points higher. Since a +5 is supposed to mean that a character is between four and eight times as able as the other, this does not seem extreme.

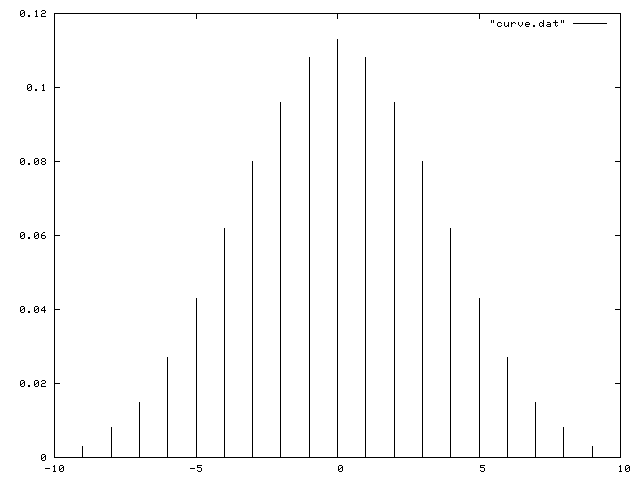

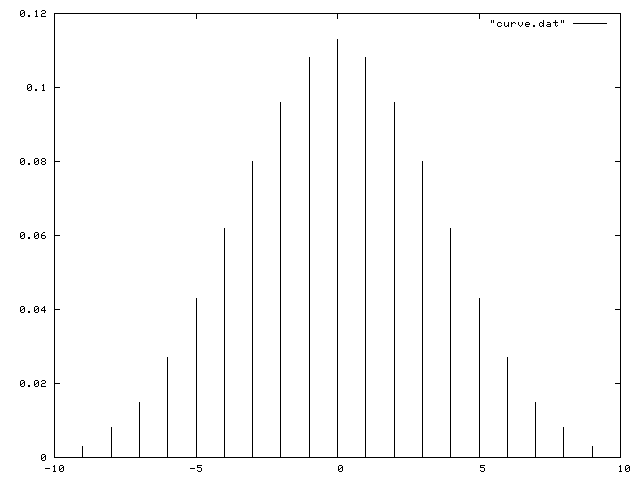

Here is what the graph of probabilities looks like for an opposed roll where the skill levels are equal (zero would mean a tie):

This graph is the reason why opposed rolls are required even for unopposed tasks such as climbing a cliff or picking a lock. If they were not - if the player simply rolled 2d6 and tried to beat a target number - the probability density graph would be more random for unopposed actions than for opposed ones.

Here is a brief table showing the probability of rolling greater than an opposing skill. Negative numbers mean that the opposing skill is inferior to yours, positive that the opposing skill is greater than yours, and zero that the skill is equal to yours. Example: to find out the probability of a skill level of 6 beating a skill level of 9, look at the probability of +3.

Multiply the probabilities p(x) by 100 to get percentages.

| Skill | p(x) |

|---|---|

| -10 | 0.99923 |

| -9 | 0.99614 |

| -8 | 0.98843 |

| -7 | 0.97299 |

| -6 | 0.94599 |

| -5 | 0.90278 |

| -4 | 0.84105 |

| -3 | 0.76080 |

| -2 | 0.66435 |

| -1 | 0.55633 |

| 0 | 0.44367 |

| 1 | 0.33565 |

| 2 | 0.23920 |

| 3 | 0.15895 |

| 4 | 0.09722 |

| 5 | 0.05401 |

| 6 | 0.02701 |

| 7 | 0.01157 |

| 8 | 0.00386 |

| 9 | 0.00077 |

| 10 | 0 |

Enough on the core mechanic. Let's examine the conflict system.

I decided not to worry much about the particular detailed differences between types of weapons or armor. I didn't want a player to have to choose a sword for tactical reasons if he really wanted to play an axe-wielding barbarian. At the same time, I didn't want players to be able to do the damage of a greatsword with a dagger. That would be unfair, as daggers have other advantages over larger weapons (they can be thrown, they are easily concealed). I settled on having the damage of a weapon determine its size.

I wanted there to be a reason why sorcerers would use foci such as wands, staves, and charms. I also wanted a rationale for why a priest or wizard is more powerful in his tower or temple than outside of it. To this end, I made all of these foci the sorcerous equivalent of weapons and armor - you can do your craft without them, but they make you more powerful.

Some games have fixed initiative - whoever has the greatest dexterity or agility or perception or whatever always gets to go first. I'm not fond of this. I prefer rolling for Initiative. In fact, I'm fond of the phrase itself: "Roll for initiative." It's cool. Its threatening. It leaves no doubt about your intentions - someone is about to get hurt.

Having a skill dedicated to Initiative in particular adds some variety to the types of fighters possible in the game. Players could create a samurai-like warrior by putting emphasis on aggressive initiative and striking, to the detriment of defense, or a fencer who concentrates on fending off an opponent while looking for an opening.

Most games have fixed character actions as well - every character gets a certain number of actions per round or turn based on their stats, skills, or level. I prefer the method used by WEG's d6 system - dynamic speed. Characters may take as many actions as they wish, but multiple actions give penalties. This adds another tactical element - do I want to do one thing as well as possible this round, or would it be better to attempt several things at once with a greater chance of failure?

Range Increments for missile weapons, types of sorcery, and senses were lifted directly from a popular fantasy game. I think they work well, so I stole them.

One design decision that hard-core wargamers will dislike is the lack of detailed movement rules. I have never been fond of using detailed maps in my roleplaying game sessions. I sometimes use maps to show the general location of characters relative to one another and to their surroundings, but I dislike games that require the game master to map things in excruciating detail. I enjoy a balance of tactical play (as determined by the characters decisions and actions) and fast-and-loose cinematics. Tactics-lite.

I also tried to stay away from lists of combat maneuvers. Such lists often seem arbitrary even when they are functional. I think it better to have a formula that allows players to design their own, and even better to have maneuevering built into the basic mechanics. I have tried to do the latter. If the player wants to "All-Out Dodge", his character simply takes a Defense action and nothing else. If the player wants to "Ferociously Attack", he simply makes one or more attack actions with no defensive ones. If he wants a balanced approach, he can make one attack action and one defend.

The "Augment" action should cover most of what is left out. It gives a player extra damage at the expense of skill, which can be explained as a called shot, a wild swing, or a nerve strike. The rationale for the extra damage is up to the player.

The rules for large-scale battles are not perfect. I wanted to throw something in that would allow large conflicts to be decided quickly, and wanted the Tactics skill to have a concrete effect on the outcome. Still, the mechanics of this section don't mesh with the rest of the game as nicely as I would like. Players can opt to ignore this in favor of playing out the large battles.

I chose to have a mix of different damage types to simulate the very different ways that characters can be harmed. I wanted it to be possible to defeat a character without killing him. This is what Stamina is for - to represent the cumulative wearing down of a character when he is beaten repeatedly. Wound levels are there to represent real damage - the kind that threatens one's life. I have seen studies that suggest there is no cumulative effect of wounds other than blood loss, so the mechanics reflect this. Your wound level, and associated penalties, is based only on the maximum amount of punishment you have taken from any single hit.

Sanity levels work like wound levels, but are meant for attacks based on overwhelming fear or mental powers.

I wanted sorcerers to have a lot of options when casting a spell. Much like initiative and speed, I did not want spell intensity, duration, area, or casting time to be permanently fixed. The rules are designed so that sorcerers may trade one for another in various ways, which I hope will lead to many different tactics and trade-offs.

I wanted players to be able to make a powerful sorcerer without needing the character to be strong or quick. To this end, all of a sorcerer's abilities are based on his mind. I also wanted sorcerous duels to be as fun as those of swordsmen. The ability to dodge or deflect spells without physically moving is part of this.

The types of sorcery were chosen to fit the setting - wild, unsubtle powers granted to mortals by gods for their own purposes. The rules for group rituals and the sacrificing of physical or mental health exist mainly to add flavor.

Setting Notes

Though my vision is a low fantasy world focused on humans and their gods, I didn't want to strictly limit other elements of classic fantasy. Amelatu sorcery (the ability to open gateways to other worlds) allows game masters to introduce non-human elements into a campaign. The fact that sorcery is required for such elements means that they can be as much or as little a part of a campaign as the game master wishes.

The otherworldly cosmology described in the text is a grab-bag of various fantasy realms that I like. I deliberately stated that there were other worlds than these so that game masters could bring in whatever manner of weirdness they desired. One could even bring in elements of the modern world, or science fiction. I wouldn't, but it could be done.

The mundane setting of the old kingdoms versus the frontier is left open by design. I gave just a brief description of various places so that game masters would have a framework on which to hang plots. There is no overarching metaplot. The details are up to you.