DESIGNER NOTES

Introduction

Fantasy is the most overdone genre in the world of RPGs. I designed Hursagmu because my system and setting tastes are unusual. I want a fantasy game that is in the middle of the great RPG debates.

Goals for the system:

The mechanics are unoriginal. Hursagmu takes elements from the Hero System, West End Games's classic d6 system, Dungeons & Dragons, GURPS, Fudge, and many others.

The setting is a mishmash of Conan, Cthulhu, Paradise Lost, Sumerian mythology, UFO lore, and The Twilight Zone.

Character Generation

The costs of traits increase with level to prevent munchkins from placing all their points into a single ability. Such characters are gods at one thing and useless at all else. The system is designed to discourage this.

The exponential increases also allow traits to be open-ended without fear that someone will have a Sorcery of 700.

This cost scheme also means that it is painless for a character to gain a small amount of any trait. Mastery, on the other hand, requires dedication.

Traits are broad for the sake of simplicity. I have tried to group different abilities together under single traits in ways that make sense. Characters are less customizable than in games with hundreds of skills, but I think the ease of character building is worth the trade. Chargen is simpler with a small number of broad traits than with a large number of narrow ones.

The trait list focuses on adventuring abilities; trade skills are abstracted. I did this so that talented craftsmen and scholars can compete in the adventuring arena. All craft skills, from blacksmithing to shoemaking, are considered part of a single trait: Craftsmanship. All academic skills are considered part of Scholarship. This is unrealistic, but I think it's fun.

The decision to leave out traits related to social dynamics was deliberate. I prefer for such situations to be resolved through roleplaying rather than dice. If you want to be beautiful and dashing, fine. If you would rather be ugly and scary, good. There are advantages and disadvantages to both.

Note that this is meant primarily for player characters - most NPCs will be specialists.

Gifts are required for the use of sorcery to prevent every character from having the ability. Gifts also allow for alien abilities.

Some may be confused by the damage metrics. Some players might think it unrealistic that their big brawny warrior has the same Health and Stamina as a scholar. Those who think this should look at the metrics from the opposite direction to see what actually happens when characters get hurt.

It's easiest to illustrate by example. Take two characters, Bob and Fred. Bob has a Constitution of 0 - completely average. Fred has a mighty Constitution of 4. What happens when either character is hit by an attack that does 6 damage? After one hit, Bob will be down 6 Health and 10 Stamina. After two hits, he will be unconscious and fairly hurt. Fred, on the other hand, will have to be hit four times by the same attack before he will fall, and will still be less injured than Bob.

So, though damage metrics are the same for every character in absolute numbers, different characters are still able to take more or less punishment based on their Constitution, Willpower, and equipment.

System Mechanics

The mechanics are meant to be easy to learn and simple to execute, yet powerful in possibility.

Goals:

Hursagmu uses opposed rolls of 2d6 + Trait as the core mechanic. This gives both sides in a contest the chance to roll dice and leads to a nice bell curve of probabilities.

Opposed rolls of 2d6 are functionally equivalent to rolling 2d6 - 2d6 or 4d6 - 14. All three methods involve four dice and give a probability distribution ranging from -10 to 10, centered on zero, with 89% of the rolls falling between -5 and 5.

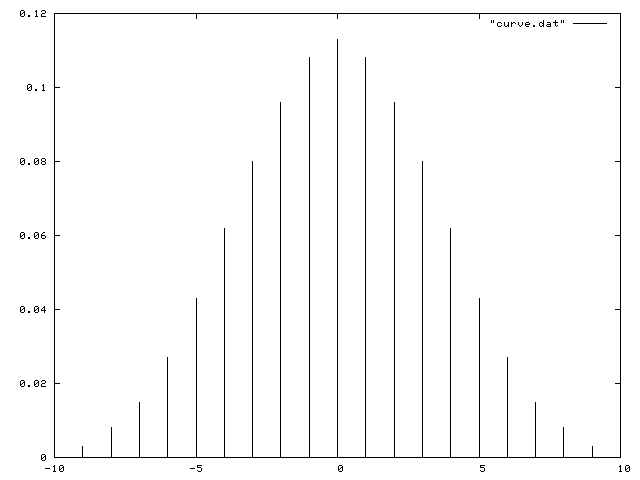

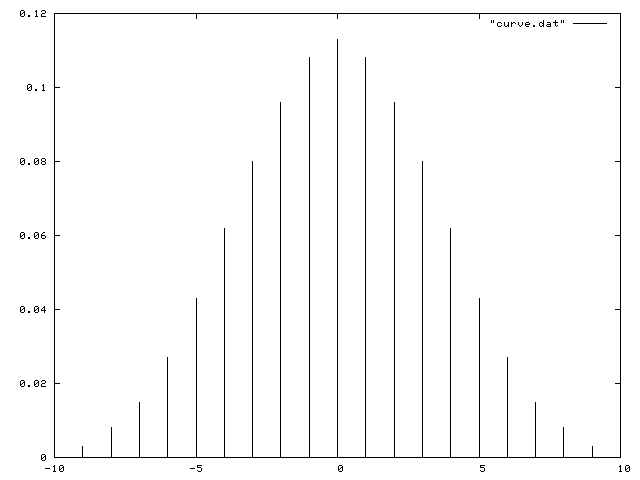

Here is what the graph of probabilities looks like for an opposed roll where the trait levels are equal (zero would mean a tie):

This graph is the reason why opposed rolls are required even for unopposed tasks such as climbing a cliff or picking a lock. If they were not - if the player simply rolled 2d6 and tried to beat a target number - then unopposed actions would be more random than opposed ones.

If players can't overcome the psychological effect of being "beaten" by the roll of an inanimate object, they may roll all four dice - but two of them should be declared negative before rolling.

Here is a brief table showing the probability of rolling greater than an opposing trait. Negative numbers mean that the opposing trait is inferior to yours, positive that the opposing trait is greater than yours, and zero that the trait is equal to yours. Example: to find out the probability of a level 6 trait beating a level 9, look at the probability of +3.

Multiply the probabilities p(x) by 100 to get percentages.

| Trait | p(x) |

|---|---|

| -10 | 0.99923 |

| -9 | 0.99614 |

| -8 | 0.98843 |

| -7 | 0.97299 |

| -6 | 0.94599 |

| -5 | 0.90278 |

| -4 | 0.84105 |

| -3 | 0.76080 |

| -2 | 0.66435 |

| -1 | 0.55633 |

| 0 | 0.44367 |

| 1 | 0.33565 |

| 2 | 0.23920 |

| 3 | 0.15895 |

| 4 | 0.09722 |

| 5 | 0.05401 |

| 6 | 0.02701 |

| 7 | 0.01157 |

| 8 | 0.00386 |

| 9 | 0.00077 |

| 10 | 0 |

The degree-of-success mechanic takes care of several things at once - there is no need for damage rolls, hit locations, special maneuvers that let weaklings do more damage, or techniques to allow a knife fighter to get through plate armor. It's all there in the Dos. It also means that trait checks are not just pass/fail; you get information on the quality of the success or failure.

The system is unconcerned with the detailed differences between types of weapons and armor. Players don't need to choose a sword for tactical reasons if what they really want is axe-wielding barbarians. At the same time, daggers shouldn't do the damage of a longsword; daggers have other advantages (small, lightweight, easily concealed, useful in grappling). Therefore, the damage of a weapon determine its size. Players choose the cosmetics.

It's common in fantasy literature for sorcerers to use wands and staves. It's also common for them to be more powerful in their towers and temples than outside them. To this end, the system treats these foci as the sorcerous equivalent of weapons and armor. Sorcery can be without them, but they make one more powerful.

Random initiative, and a trait dedicated to it, adds some variety to the types of tactics possible in the game. Players could create a samurai-like warrior by putting emphasis on aggressive initiative and striking or a fencer who concentrates on fending off an opponent while seeking an opening.

The system avoids lists of combat maneuvers, opting instead for rules that allow players to create their own.

There are a mix of damage metrics to simulate the different ways characters can be harmed. It should be possible to defeat a character without killing him. This is what Stamina is for - to represent the cumulative wearing down of a character. Health exists to represent real damage - the kind that threatens one's life. Sanity is there to represent Lovecraftian shocks to the psyche.

Sorcerers ought to have options when casting a spell so that supernatural duels are as exciting as physical ones. Spell intensity, duration, area, and casting time should be flexible. The rules are designed so that sorcerers may trade one for another in various ways. This will hopefully lead to interesting tactics.

Powerful sorcerers need not be strong or quick - those in stories are often old and feeble. Thus, all of a sorcerer's abilities are based on his mind. The ability to defy or deflect spells without physically moving is part of this.

The types of sorcery were chosen to fit the setting - wild, unsubtle powers granted to mortals by gods for their own purposes. The rules for group rituals and sacrificing physical or mental health exist to add flavor.

Setting Notes

Though my vision is a low fantasy world focused on humans and their gods, I don't want to strictly limit other elements of classic fantasy. Amelatu sorcery (the ability to open gateways to other worlds) allows game masters to introduce non-human elements into a campaign. The fact that sorcery is required for such elements means that they can be as much or as little a part of a campaign as the game master wishes.

The otherworldly cosmology described in the text is a grab-bag of various fantasy realms. It states that there are "other worlds than these" so that game masters can bring in whatever manner of weirdness they desire.

The mundane setting of the old kingdoms versus the frontier is left open by design. The brief descriptions of various places exist so that game masters have a framework on which to hang plots. There is no overarching metaplot. The details are up to you.